Switching from a brand-name drug to a generic version is usually safe - and saves money. But for NTI drugs, that simple swap can be dangerous. NTI stands for Narrow Therapeutic Index. These are medications where the difference between a helpful dose and a toxic one is razor-thin. A little too much, and you risk serious harm. A little too little, and the treatment fails. That’s why changing brands, even to an FDA-approved generic, isn’t just a paperwork change - it’s a medical risk.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

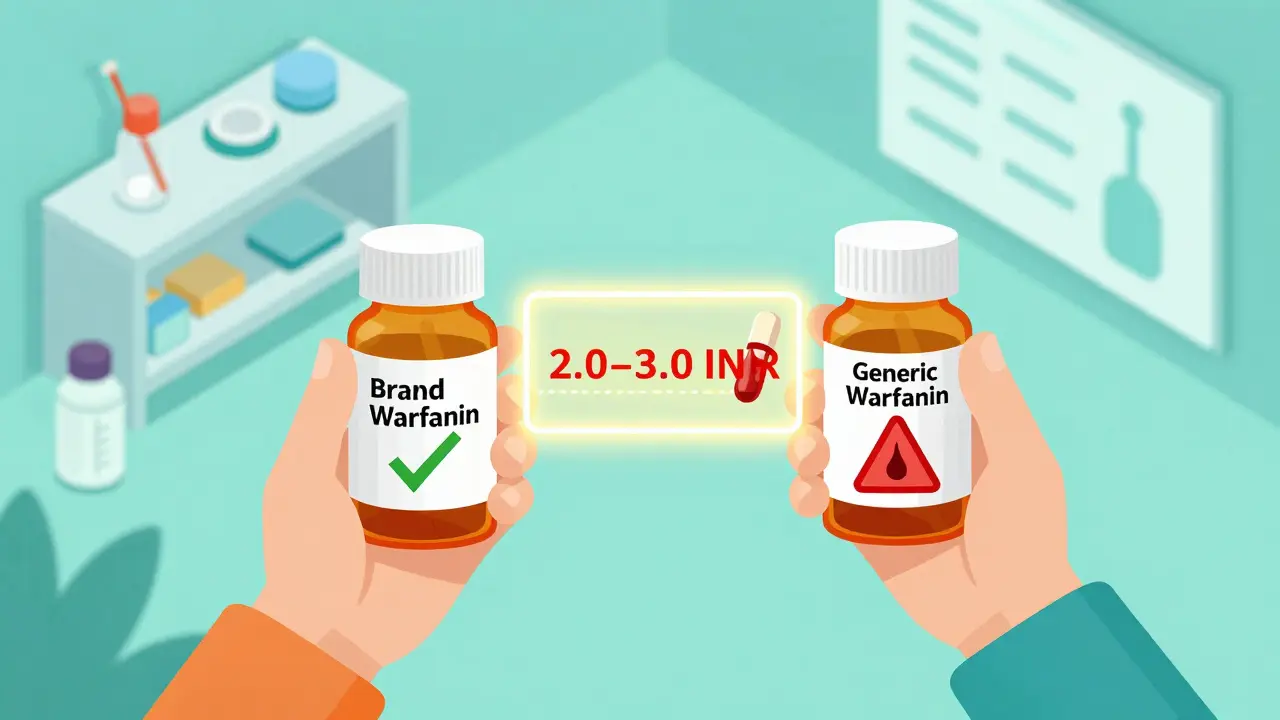

An NTI drug has a therapeutic window so narrow that even small changes in blood levels can cause big problems. The FDA defines these drugs as ones where tiny differences in dose or concentration can lead to serious treatment failures or dangerous side effects. For example, warfarin - a blood thinner - needs to keep your INR between 2.0 and 3.0. Go below 2.0, and you could get a clot. Go above 3.0, and you could bleed internally. There’s no room for error.

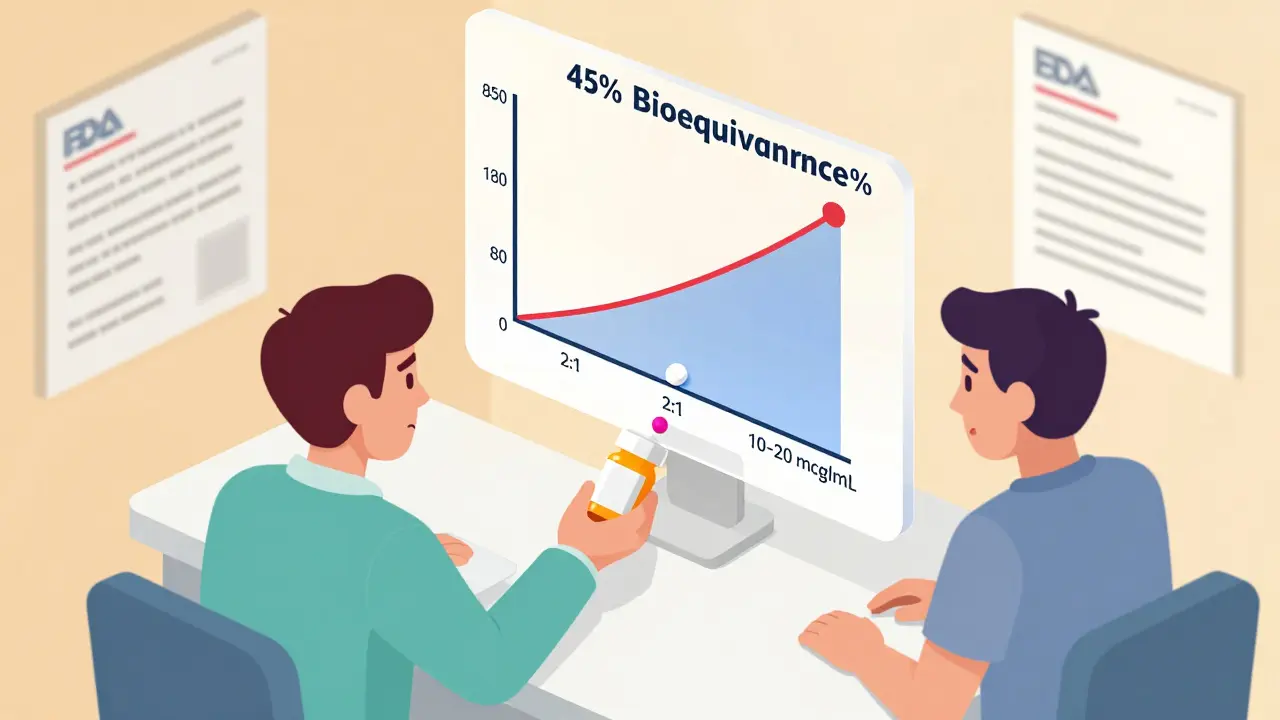

Phenytoin, used for seizures, works the same way. The safe range is 10 to 20 mcg/mL. Above 20, you get dizziness, unsteady walking, and even confusion. Below 10, seizures return. Lithium for bipolar disorder? Same story. Too high? Kidney damage, tremors, coma. Too low? Depression returns. These aren’t hypothetical risks. Real patients have had breakthrough seizures, strokes, and fatal overdoses after switching generics.

The Bioequivalence Gap

The FDA requires generic drugs to be bioequivalent to the brand-name version. That means the generic must deliver 80% to 125% of the active ingredient compared to the original. Sounds fair, right? But here’s the problem: for NTI drugs, that 45% swing is too wide. If the safe range is only a 2:1 ratio - say, 10 to 20 mcg/mL - then a 25% increase in absorption could push you over the edge. A 20% drop could make the drug useless.

Warfarin is the classic example. One study showed patients switching from Coumadin to a generic version had INR levels that dropped into the subtherapeutic range - meaning their blood wasn’t thin enough. Another study found no significant change. The inconsistency isn’t random. It’s because different generic manufacturers use different fillers, coatings, and manufacturing processes. These don’t change the active ingredient, but they can change how fast or how well your body absorbs it. For most drugs, that doesn’t matter. For NTI drugs, it does.

Real Cases, Real Consequences

In the 1980s, patients on phenytoin started having seizures after switching to a generic version. Doctors found their blood levels had dropped. The generic was technically bioequivalent - but not clinically equivalent. In another case, a patient on carbamazepine had a seizure after switching to a different generic. Blood tests showed the concentration had fallen below the minimum effective level. Neither case was due to patient noncompliance. Neither was due to a dosing error. It was the switch.

Opioids like methadone are another concern. In opioid-naïve patients, the difference between pain relief and respiratory depression can be as small as 2:1. Switching to a generic with slightly higher bioavailability could cause someone to stop breathing. Switching to one with lower bioavailability could leave them in unbearable pain. Both outcomes are life-altering - or fatal.

Why Do Pharmacists Still Switch Them?

Many states allow automatic substitution of generics unless the doctor says “do not substitute.” Pharmacists are trained to save money and follow protocol. Most believe generics are interchangeable. A 2019 survey showed most pharmacists are confident in NTI generics. But that confidence drops among those working in smaller, independent pharmacies - and among female pharmacists. Why? Because they’ve seen the consequences firsthand. They’ve had patients come back with bleeding, seizures, or uncontrolled pain after a switch.

The American Medical Association (AMA) says the decision should be made by the prescribing physician - not the pharmacist or insurance company. Yet, many patients don’t know they’re being switched. They pick up their prescription, see a different label, and assume it’s the same. They don’t know to ask.

What Should Patients Do?

If you take an NTI drug, don’t assume your generic is safe to switch. Ask your doctor: Is this drug on the NTI list? If yes, ask them to write “dispense as written” or “no substitution” on the prescription. That legally blocks the pharmacy from swapping it without your doctor’s approval.

Keep a list of all your medications - including dosages and brands - and share it with every provider you see. If you’re switched to a generic, ask for a blood test within a week. For warfarin, check your INR. For phenytoin, ask for a serum level test. Don’t wait for symptoms. Small changes in blood levels can build up quietly.

Also, stick to one pharmacy. If you switch pharmacies, you might get a different generic version - and another unpredictable shift in absorption. Consistency matters more than cost.

The Bigger Picture

NTI drugs make up about 15-20% of commonly prescribed medications. That includes warfarin, digoxin, lithium, phenytoin, theophylline, and some seizure and pain meds. These aren’t rare. Millions of people take them. And the FDA still says the 80-125% bioequivalence range is acceptable. But experts disagree. Some say NTI drugs shouldn’t be substituted at all. Others say tighter limits - like 90-111% - should be required.

The tension is clear: generics save billions. But patient safety can’t be a cost-cutting metric. The current system treats NTI drugs like any other medication. It shouldn’t. We monitor blood levels for these drugs for a reason. Because the margin for error is not just small - it’s life-or-death.

What’s Next?

Some experts are calling for more real-world data. The American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics wants studies that track outcomes - not just blood levels - after generic switches. Are patients having more hospital visits? More ER trips? More deaths? That’s the kind of evidence needed to change policy.

Until then, the safest approach is simple: if you’re on an NTI drug, don’t let your medication be switched without your doctor’s say-so. Know your drug. Know your numbers. And never assume a generic is the same just because it’s cheaper.

Are all generic drugs unsafe for NTI medications?

No. Many patients take generic NTI drugs without issues. But the risk is higher than with other medications. The problem isn’t that generics are defective - it’s that the bioequivalence standard (80-125%) is too broad for drugs with a narrow therapeutic window. Some patients tolerate switches fine. Others don’t. That unpredictability is why caution is needed.

Which drugs are considered NTI drugs?

Common NTI drugs include warfarin, phenytoin, lithium, digoxin, theophylline, carbamazepine, levothyroxine, and methadone. Some sources also include cyclosporine and tacrolimus. These are listed by the FDA and state pharmacy boards. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist or doctor for a list.

Can I switch back to the brand-name version if I have problems?

Yes. If you notice new side effects, worsening symptoms, or abnormal blood test results after switching to a generic, contact your doctor immediately. You can request to return to the brand-name drug. Insurance may require prior authorization, but your doctor can help you appeal. Your health is more important than cost savings.

Why doesn’t the FDA require tighter standards for NTI generics?

The FDA says current standards are adequate, based on available data. But many experts disagree. The agency has recommended tighter limits for NTI drugs since 2010, yet no official change has been made. Part of the delay is due to lack of large-scale outcome studies. Without clear evidence of harm, regulators hesitate to change rules - even when clinical experience suggests caution.

Should I avoid generics entirely if I’m on an NTI drug?

Not necessarily. Many people successfully use generic NTI drugs. But you need to be proactive: get your blood levels checked after any switch, stick with the same pharmacy, and never let a substitution happen without your doctor’s approval. If your doctor recommends the brand, follow that advice. Your safety isn’t worth gambling on cost savings.