Medicaid spends billions on prescription drugs every year - but most of that money isn’t going to brand-name pills. In 2023, generic drugs made up 84.7% of all Medicaid prescriptions, yet accounted for just 15.9% of total drug spending. That’s the power of generics: they’re cheap, effective, and essential to keeping Medicaid budgets from collapsing. But even with that savings, states are still fighting to do more. With drug prices rising, supply shortages growing, and PBMs taking bigger cuts, states are rolling out new strategies - and some are working better than others.

How Medicaid Gets Its Generic Drug Discounts

The foundation of all this cost control is the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), created in 1990. Under this federal rule, drugmakers must give Medicaid a rebate on every generic drug they sell. For generics, that rebate is 13% of the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP), or the difference between AMP and the best price offered to other buyers - whichever is higher. It’s not a negotiation. It’s a formula. And it’s the reason Medicaid pays far less than what you’d pay at your local pharmacy.

But here’s the catch: states can’t negotiate extra discounts on generics like they can with brand-name drugs. That means if a manufacturer hikes the price of a generic antibiotic, Medicaid’s rebate doesn’t automatically go up to match. States are stuck with the federal formula. So while MDRP saves billions, it doesn’t stop price spikes - which is why states had to start looking elsewhere.

Maximum Allowable Cost Lists: The Most Common Tool

Forty-two states now use Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists to cap what they pay for generic drugs. These lists set a price ceiling for each generic medication - say, $5 for metformin or $10 for lisinopril. If a pharmacy tries to bill Medicaid for more than that, the claim gets denied or adjusted down.

MAC lists are simple, effective, and widely used. But they’re also messy. Generic drug prices swing wildly. A pill that costs $2 one month might jump to $8 the next due to a shortage or manufacturer change. And many states update their MAC lists only once a month - or even less. That means pharmacies sometimes get paid less than what they paid for the drug, or worse, get stuck with claims rejected because the MAC didn’t reflect a recent price drop.

A 2024 survey of 1,200 independent pharmacies found that 74% had experienced delayed payments or claim rejections because of MAC list mismatches. That’s not just a billing headache - it’s pushing small pharmacies to drop Medicaid contracts. And when pharmacies drop out, patients lose access.

Generic Substitution and Therapeutic Interchange

Forty-nine states require pharmacists to substitute a generic version whenever it’s available - even if the doctor didn’t specifically write for it. That’s called mandatory generic substitution. It’s not controversial. It’s common sense. Why pay $150 for a brand-name statin when the generic works just as well for $5?

But some states go further. Nineteen states use therapeutic interchange policies. That means if a patient is on a more expensive generic, the state can automatically switch them to a cheaper one in the same drug class - say, from one generic blood pressure pill to another - without needing a new prescription. It’s not just about price. It’s about picking the most cost-effective option within a category.

These policies work best when paired with clear clinical guidelines. When done right, they save money without hurting outcomes. When done poorly - say, by switching patients to a drug they’ve had bad reactions to - they cause confusion, refill delays, and even hospital visits.

Price Gouging Laws: Targeting Unfair Hikes

Not all generic price spikes are market-driven. Sometimes, they’re deliberate. In 2020, Maryland passed a law that made it illegal for manufacturers to raise the price of a generic drug without a valid reason - like a new formulation or increased production cost. If a company hikes the price of a decades-old antibiotic by 300% with no new data to justify it, they can be fined.

That’s the anti-price-gouging model, now adopted in several other states including California, Colorado, and Vermont. These laws target manufacturers who exploit market gaps - like when only one company makes a drug and no one else can enter the market. It’s not about controlling prices. It’s about stopping fraud.

But enforcement is tricky. States don’t have the resources to audit every drug price change. And manufacturers often hide behind vague justifications like “raw material costs.” Still, these laws send a message: you can’t just raise prices because you can.

The PBM Problem: Who’s Really Profiting?

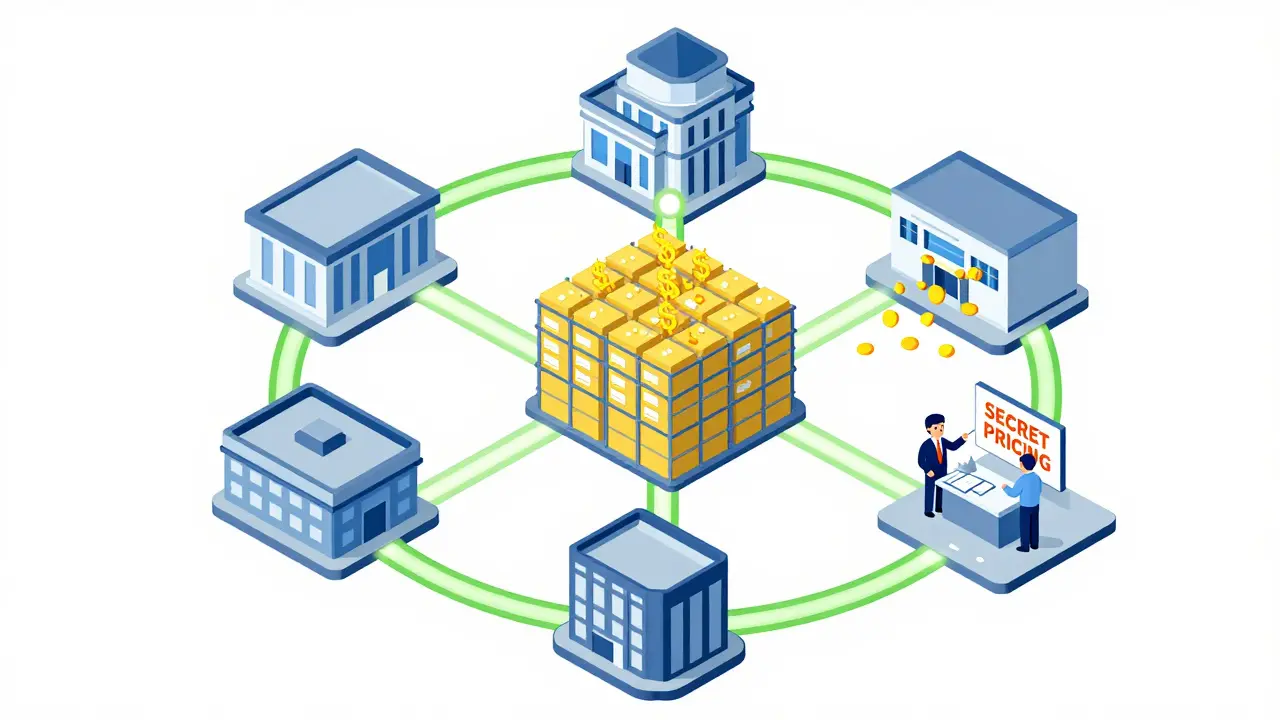

Thirty-three states outsource their Medicaid pharmacy benefits to Pharmacy Benefit Managers - companies like OptumRx, Magellan, and Conduent. These firms negotiate discounts, manage formularies, and process claims. Sounds good, right?

Not always. PBMs often keep a cut of the savings instead of passing them back to Medicaid. They use secret pricing deals with manufacturers. They charge pharmacies fees to be on a formulary. And they sometimes delay payments or deny claims over tiny discrepancies.

In 2024, 27 states started requiring PBMs to disclose how much they actually paid for generic drugs. Nineteen states now demand transparency on acquisition costs. That’s a big shift. If Medicaid knows what a drug really costs, it can stop overpaying. But PBMs are fighting back - with lawsuits, lobbying, and threats to pull out of state contracts.

Supply Chain Shortages and Stockpiling

In 2023, 23 states reported shortages of critical generic drugs - antibiotics, insulin, heart meds - with each shortage lasting an average of 147 days. Why? Because the generic drug market is dominated by just three manufacturers who control 65% of injectable generics. When one factory shuts down, the whole system stumbles.

Twelve states passed new laws in 2024 to build emergency stockpiles of essential generics. Oregon and Texas are leading the way, storing months’ worth of key medications. Maryland created a public-private partnership to secure alternative suppliers. These aren’t just backup plans - they’re insurance policies against future crises.

But stockpiling costs money. And storing drugs requires temperature control, security, and rotation. It’s not a quick fix. But when a shortage hits, having even a few weeks’ supply can keep patients alive.

What’s Next? The Future of Generic Drug Control

By 2025, 15 more states are expected to introduce bills targeting generic drug pricing. The focus is shifting from just managing costs to securing supply. States are forming multi-state purchasing pools - like the one led by Oregon and Washington - to buy 47 high-volume generics together and get bulk discounts.

At the same time, the federal government is stepping back. The Medicare Two Dollar Drug List Model was scrapped in March 2025. That means states are now the main players in drug pricing reform.

But there’s a real risk. If states push too hard - setting prices too low, cutting rebates, or over-regulating - manufacturers may stop making certain generics altogether. The Congressional Budget Office warns that overly aggressive policies could reduce availability and actually raise Medicaid spending by 2.3% as patients shift to pricier alternatives.

The goal isn’t to drive prices to zero. It’s to keep them fair, stable, and predictable. To make sure that a $3 generic heart pill doesn’t become a $300 one overnight. To make sure that when a patient needs their medicine, it’s there - and affordable.

State Strategies at a Glance

| Strategy | States Using It | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) Lists | 42 | Reduces per-pill costs; risk of access delays if outdated |

| Mandatory Generic Substitution | 49 | Maximizes use of lowest-cost options; minimal resistance |

| Anti-Price-Gouging Laws | 9 | Targets unfair hikes; hard to enforce |

| PBM Transparency Requirements | 27 | Reduces hidden profits; facing legal pushback |

| Therapeutic Interchange | 37 | Improves cost-efficiency; needs clinical oversight |

| Strategic Stockpiling | 12 | Builds resilience; costly to maintain |

| Multi-State Purchasing Pools | 5 | Leverages buying power; growing trend |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why don’t Medicaid rebates stop generic drug price spikes?

The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program gives a fixed percentage rebate (13% for generics), not a fixed dollar amount. If a manufacturer raises the price of a generic drug, Medicaid pays more - and the rebate goes up proportionally, but doesn’t offset the full increase. States can’t negotiate extra discounts on generics like they can with brand-name drugs, so they’re stuck with the federal formula.

Can states force pharmacies to use cheaper generics?

Yes. Forty-nine states require pharmacists to substitute a generic drug when it’s available and FDA-approved as equivalent - even if the prescription says brand name. This is called mandatory generic substitution. It’s legal, common, and saves money without affecting effectiveness.

What’s the biggest challenge states face with generic drug pricing?

The biggest challenge is balancing cost control with access. MAC lists and price caps can save money, but if they’re not updated quickly enough, pharmacies can’t afford to stock the drugs - and patients go without. Meanwhile, supply chain issues and manufacturer consolidation mean shortages are becoming more common, making it harder to rely on just one source.

Do generic drug price controls cause shortages?

They can. If states set reimbursement rates too low, manufacturers may stop producing certain generics because they’re not profitable. The Congressional Budget Office warns that overly aggressive price controls could reduce availability, leading patients to switch to more expensive brand-name drugs - which could end up costing Medicaid more in the long run.

Are PBMs helping or hurting Medicaid’s efforts to cut drug costs?

It’s mixed. PBMs negotiate discounts and handle claims efficiently, but they often keep a portion of those savings instead of passing them to Medicaid. Many states now require PBMs to disclose how much they pay for drugs - and some are cutting ties with PBMs that don’t show transparency. The trend is moving toward state control, not outsourcing.

What’s the most effective state policy for lowering generic drug costs?

The most effective approach combines multiple strategies: mandatory generic substitution, updated MAC lists, anti-price-gouging laws, and PBM transparency. States like Maryland and Oregon, which use all these tools together, have seen the biggest savings without major access issues. No single policy is enough - it’s the combination that works.

What States Should Do Next

States need to stop treating generic drugs like an afterthought. They’re the backbone of Medicaid’s pharmacy budget. The next step is building smarter systems: real-time price tracking, automated MAC updates, and direct contracts with manufacturers to bypass PBMs entirely. Some states are already testing this - and the results are promising.

But it’s not just about money. It’s about trust. Patients need to know their medicine will be there - and affordable. States that get this right won’t just save billions. They’ll protect the health of millions.