Global Drug Safety Comparison Tool

Enter a drug name to see how major regulatory agencies approve it and issue safety warnings

Every pill you take, every injection you receive, every inhaler you use - it didn’t just appear on a pharmacy shelf. Behind each medicine is a complex web of rules, inspections, and decisions made by governments to decide if it’s safe enough for you to use. But here’s the thing: drug regulation isn’t the same everywhere. What’s approved in the U.S. might be pulled in Europe. A warning issued in Australia might never reach a patient in Nigeria. And that’s not a glitch - it’s the system.

How the U.S. FDA Approves Drugs: Speed, Clarity, and Central Control

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) runs a tightly centralized system. One agency. One approval process. If a drug gets the green light from the FDA, it can be sold nationwide without needing separate sign-offs from each state. That’s efficiency. In 2022, the FDA approved new drugs in an average of 10.2 months - faster than most other major regulators. This structure means clear accountability. When a drug causes harm, you know exactly where to look. The FDA’s MedWatch system lets doctors and patients report side effects directly, and 83% of users in a 2022 survey said these alerts were timely and easy to act on. The agency also publishes detailed guidance documents - 312 of them - and 92% of pharmaceutical companies rated them as clear and useful. But there’s a cost. The FDA’s single-point system can become a bottleneck. During the pandemic, review times jumped by 37% because every application had to go through one office. And while the agency moved quickly on life-saving drugs like mRNA vaccines, it’s been slower to approve certain rare disease treatments compared to Europe. In 2022, the FDA approved 18.3% more rare disease therapies than the EMA - but the EMA approved 12.7% more cancer drugs. Why? Different risk tolerances. The FDA tends to demand stronger proof of benefit before approving, while the EMA sometimes accepts smaller benefits if the disease has no other options.The European Union: A Networked System with National Flexibility

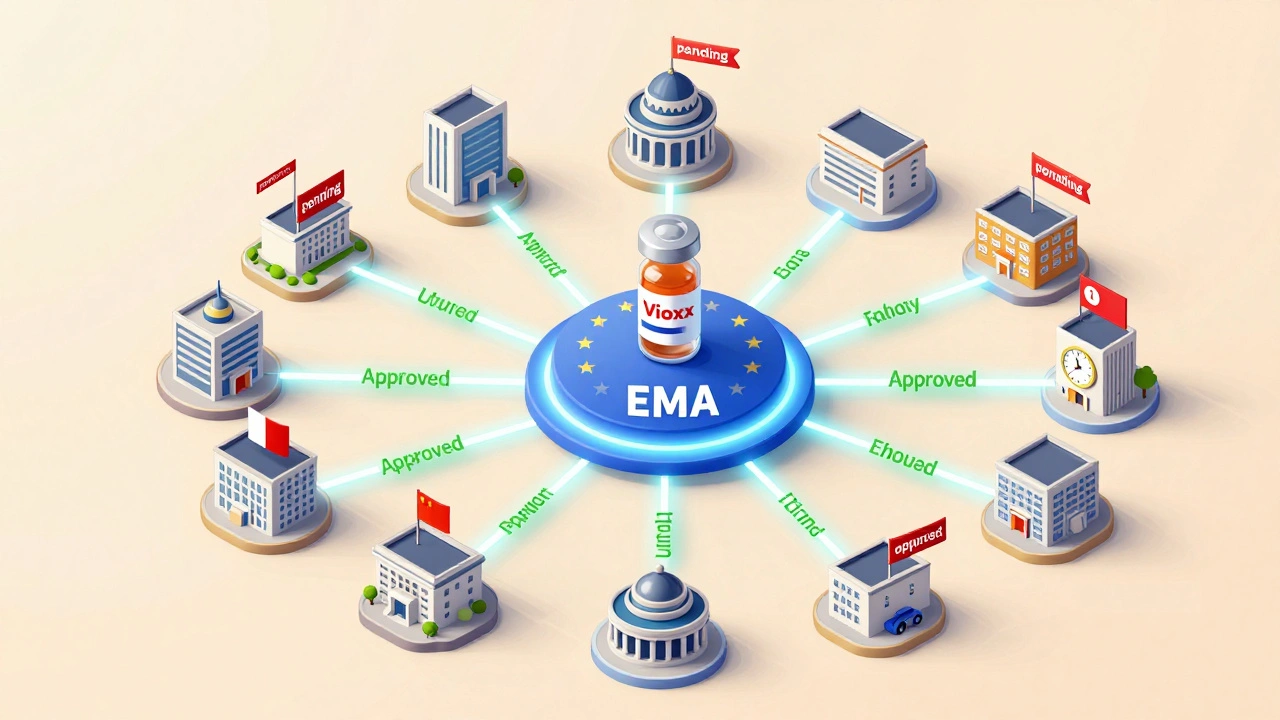

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) doesn’t act alone. It’s the hub of a network of 27 national regulators. For new, complex drugs - like biologics or gene therapies - companies apply for a single EU-wide approval through the EMA. But for older, generic medicines, each country can make its own decision. This hybrid model gives flexibility but creates chaos for drugmakers. A 2021 survey by the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) found that 68% of companies struggled with the complexity of navigating different national rules. Approval times are longer too: 12.7 months on average for centralized applications. But European doctors often praise the transparency. About 71% said EMA’s benefit-risk assessments were comprehensive and easy to understand - compared to 63% for FDA documents. The EU’s strength is in its ability to act fast when safety issues arise. When the painkiller Vioxx was pulled in 2004, 22 EU countries coordinated their responses within 14 days. In the U.S., it took 28. Why? Because the EU’s networked structure lets multiple regulators act in parallel. The EU also requires stricter quality risk management under Annex 20 of its GMP rules, and 98.7% of EU-based manufacturers met those standards in 2022 - higher than the 92.3% compliance rate in the U.S.Canada and Australia: Middle Ground with Global Ties

Canada’s Health Canada and Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) sit between the U.S. and EU models. Both have strong, independent agencies with binding laws. Canada’s Food and Drugs Act and Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 give them full legal authority over what gets sold. What’s interesting is how they’ve aligned with bigger systems. After signing a Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) with the EU in 2019, Canada saw 87% alignment with EU safety decisions. Australia, meanwhile, matches the FDA on 79% of safety alerts but only 63% with the EMA. That tells you something: Australia leans more toward U.S. standards, while Canada is syncing up with Europe. Both countries also use real-world data to monitor drugs after they’re on the market. The TGA, for example, tracks adverse events through its database and updates guidelines based on actual patient outcomes - not just clinical trial numbers. That’s a growing trend: regulators are moving from lab-based approvals to real-world evidence.

The World Health Organization: Guidelines, Not Laws

The WHO doesn’t approve drugs. It doesn’t inspect factories. It doesn’t issue recalls. But it sets the global baseline. The WHO’s Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) guidelines are used by more than 150 countries - especially in places without strong regulatory systems. In Africa, where the African Medicines Agency (AMA) launched in 2021, only 37% of manufacturing facilities meet even basic GMP standards. In India, the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) ramped up inspections by 40% in 2022 after new GMP rules came in. These countries rely on WHO standards because they don’t have the resources to build their own from scratch. The WHO’s 2023 Global Benchmarking Tool rated 67 countries as having a “functional” regulatory system - meaning they can approve drugs, inspect factories, and monitor safety. But “functional” doesn’t mean “strong.” Many low-income nations still struggle with delayed alerts, poor data collection, and lack of trained staff. The International Alliance of Patients’ Organizations found that only 42% of patients in countries like Nigeria and Bangladesh receive safety warnings in time - leading to preventable harm.Why Safety Warnings Don’t Match Up

Here’s the most startling fact: only 10.3% of safety warnings issued by the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and Australia agree on the same drugs. That means if a drug is flagged as dangerous in one country, it’s likely still being sold without warning in others. Why? Because regulators weigh risk differently. The FDA might see a 1 in 10,000 chance of liver damage as too high. The EMA might say, “But this drug helps patients who have no other options.” Australia might wait for more data. Canada might act fast if it matches EU findings. This isn’t just confusing - it’s dangerous. When patients travel, get care abroad, or buy medicines online, they don’t know which country’s rules apply to them. Dr. Thomas Frieden, former CDC director, called this fragmentation “a dangerous gap” that puts millions at risk. The Institute of Medicine estimates that therapeutic confusion from mismatched warnings could affect up to 200 million patients annually.