When someone hears the word brain tumor, fear often comes before understanding. But not all brain tumors are the same. Some grow slowly over years. Others spread aggressively within weeks. The difference isn’t just in how they look under a microscope-it’s in their genes, their behavior, and how doctors now treat them. The way we classify and treat brain tumors has changed dramatically since 2021, when the World Health Organization released its fifth edition of the Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System (WHO CNS5). This isn’t just a technical update-it’s reshaping survival rates, treatment choices, and even how patients plan their lives after diagnosis.

What Are the Main Types of Brain Tumors?

Brain tumors aren’t one disease. They’re dozens, each with different origins, behaviors, and names. The most common are gliomas, which start in glial cells-the supportive tissue around neurons. These include astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and glioblastomas. Then there are meningiomas, which grow from the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord. These are often benign but can still cause serious problems if they press on critical areas.

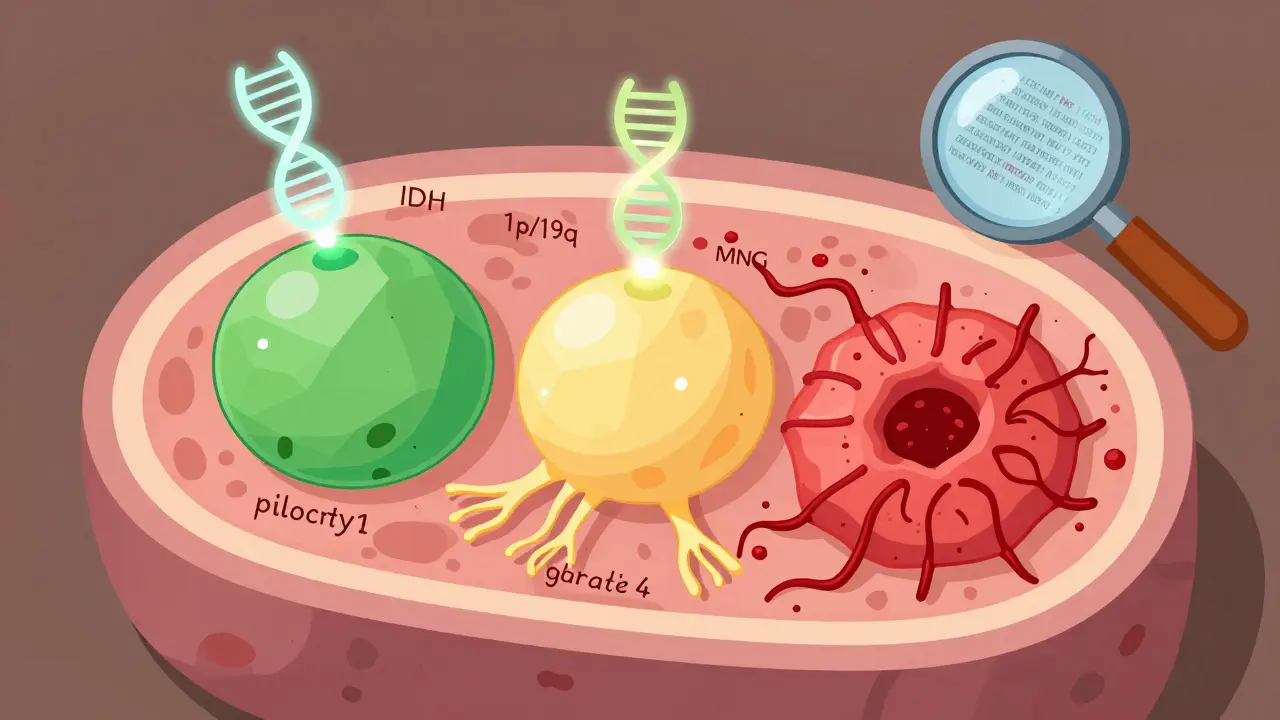

For adults, glioblastoma (grade 4) is the most common malignant brain tumor, making up more than half of all gliomas. It’s fast, invasive, and hard to remove completely. Oligodendrogliomas, on the other hand, tend to grow slower and respond better to treatment-especially when they carry a specific genetic marker: the 1p/19q codeletion. Astrocytomas can range from slow-growing (grade 2) to deadly (grade 4), depending on whether they have mutations in the IDH gene. That’s a big deal. An IDH-mutant glioblastoma isn’t treated the same way as an IDH-wildtype one. The difference? Median survival jumps from 14.6 months to over 31 months.

Meningiomas are different again. They’re graded 1 to 3, but even grade 3 meningiomas rarely spread outside the brain. Their danger comes from size and location. A grade 1 meningioma near the optic nerve can cause blindness. A grade 3 one might invade bone or trigger seizures. The key takeaway: knowing the type isn’t enough anymore. You need to know the molecular profile.

How Brain Tumors Are Graded: From 1 to 4

Grading tells you how aggressive a tumor is. It’s not about size-it’s about how abnormal the cells look and how fast they’re dividing. The WHO uses four grades, and they’re based on both what the pathologist sees under the microscope and what the lab finds in the DNA.

Grade 1 tumors, like pilocytic astrocytomas, look almost normal. They grow slowly, have clear edges, and can often be cured with surgery alone. Grade 2 tumors, such as diffuse astrocytomas, are trickier. The cells are slightly abnormal and start creeping into healthy brain tissue. They don’t spread like cancer, but they often come back as higher-grade tumors if not treated properly.

Grade 3 tumors, called anaplastic, are actively malignant. The cells are multiplying rapidly, invading nearby areas, and showing signs of chaos under the microscope. These require radiation and chemotherapy after surgery. Grade 4 is the worst. Glioblastoma, the most common grade 4 tumor, has dead centers (necrosis), abnormal blood vessels, and cells that divide like wildfire. Even with treatment, median survival is under 15 months-for the IDH-wildtype version.

Here’s where WHO CNS5 changed everything. Before 2021, an anaplastic astrocytoma was automatically grade 3. Now, it’s not that simple. A tumor might be an astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, and graded as 3-but it behaves very differently from an IDH-wildtype tumor. The grading is now tied to the tumor type, not just the appearance. That’s why pathologists now say things like: “This is an oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant, 1p/19q-codeleted, WHO grade 2.” Every word matters.

How Molecular Testing Is Changing Everything

Before 2021, a brain tumor diagnosis relied mostly on how cells looked under a microscope. Now, molecular testing is mandatory. Three key tests are done on every biopsy:

- IDH mutation status: If the tumor has a mutation in the IDH1 or IDH2 gene, it’s more likely to respond to treatment and live longer. About 80% of grade 2 and 3 gliomas have this mutation.

- 1p/19q codeletion: This genetic deletion is a hallmark of oligodendrogliomas. Tumors with it respond dramatically better to chemotherapy, especially PCV (procarbazine, lomustine, vincristine).

- MGMT promoter methylation: This tells doctors if the tumor is likely to respond to temozolomide, the standard chemo drug. When methylated, survival improves by months.

These aren’t optional extras-they’re required for accurate diagnosis. The FDA approved the Ventana IDH1 R132H antibody in 2021, cutting test time from weeks to just two days. Before, waiting for genetic results could delay treatment by over a month. Now, patients often get a full diagnosis within a week.

But it’s not perfect. Not every hospital has the equipment or trained staff. A 2022 study found pathologists needed to review nearly 18 cases before they could reliably apply the new WHO CNS5 system. And costs? Molecular testing adds $3,200 to $5,800 to the diagnostic bill. For many, insurance covers it-but not everywhere.

What Treatments Are Used Today?

Treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all anymore. It’s a mix of surgery, radiation, chemo, and now targeted drugs-all chosen based on tumor type and molecular profile.

For low-grade tumors (grades 1-2), surgery is often the first step. If the tumor is fully removed, some patients don’t need anything else. But if it’s in a sensitive area-or if it’s IDH-mutant-doctors may recommend observation with regular MRIs, or early radiation and chemo to delay progression.

For high-grade tumors (grades 3-4), the standard has been the Stupp protocol: surgery, then radiation plus daily temozolomide, followed by six months of maintenance chemo. It’s brutal, but it’s the baseline. For IDH-wildtype glioblastoma, survival is still short. But for IDH-mutant grade 4, survival nearly doubles.

And now, there’s a breakthrough. In June 2023, the FDA approved vorasidenib for IDH-mutant grade 2 gliomas. In the INDIGO trial, patients on vorasidenib went 27.7 months without their tumor growing-more than double the 11.1 months for those on placebo. This is the first drug approved specifically for low-grade gliomas that doesn’t rely on chemo or radiation. It’s taken orally. Side effects are mild. For a 32-year-old patient, this could mean years of normal life instead of years of treatment.

Other promising options include the CODEL trial, testing combined chemo for oligodendrogliomas, and liquid biopsies-blood or spinal fluid tests that detect tumor DNA. In a 2023 study, these tests spotted tumor DNA in 89% of cases, offering a way to monitor treatment without repeated brain surgeries.

What Patients Are Really Experiencing

Behind every statistic is a person. One Reddit user, diagnosed with a grade 2 oligodendroglioma at age 32, had 72 hours to decide whether to freeze eggs before surgery. Another, labeled “GBMWarrior87,” got 18 months of progression-free survival with vorasidenib-longer than the average 14.6 months offered by standard treatment.

But many still face delays. A 2022 UK survey found 68% of patients waited more than eight weeks for a diagnosis. Low-grade tumor patients waited an average of 14.2 weeks. That’s not just frustration-it’s fear, uncertainty, and lost time. And misinformation is common. One study found 42% of patients thought “grade 2” meant a 20% chance of survival. It doesn’t. Grade 2 means slow-growing. Many live for decades.

What patients need most isn’t just treatment-it’s clarity. Clear explanations of what the grade means. What the molecular results mean. What their options are. That’s why organizations like the National Brain Tumor Society and the Brain Tumour Charity now offer free, plain-language guides. They’re helping people move from panic to planning.

What’s Next for Brain Tumor Care?

The future is precision. The WHO CNS5 system is already being updated with data from clinical trials like INDIGO and CODEL. Liquid biopsies are getting better. Researchers are testing vaccines that train the immune system to attack IDH-mutant cells. And AI is being trained to read MRI scans and predict tumor type before a biopsy is even taken.

But progress isn’t automatic. It depends on access. A patient in rural Wales won’t get the same molecular testing as someone in London or Boston unless systems are upgraded. Clinical trials still only reach a fraction of patients. And the cost of new drugs-like vorasidenib-could limit availability in public health systems.

Still, the direction is clear: brain tumors are no longer defined by where they are or how they look. They’re defined by what’s inside them-the mutations, the markers, the biology. And treatment is following suit. What was once a single label-“glioblastoma”-is now a spectrum of possibilities. And for the first time, patients have real hope-not just survival, but time.

What does a grade 2 brain tumor mean?

A grade 2 brain tumor is considered low-grade, meaning the cells look only slightly abnormal under a microscope and grow slowly. These tumors can infiltrate nearby brain tissue but rarely spread to other parts of the body. They often recur, sometimes as higher-grade tumors, so ongoing monitoring or treatment after surgery is common. Molecular testing (like IDH mutation status) now plays a key role in predicting behavior and guiding treatment.

Is a grade 4 brain tumor always fatal?

Grade 4 brain tumors, like glioblastoma, are aggressive and currently incurable. The median survival with standard treatment is about 14.6 months for IDH-wildtype tumors. But outcomes vary. IDH-mutant grade 4 astrocytomas have a median survival of over 31 months. New treatments like vorasidenib and targeted therapies are extending survival for some patients. While still serious, grade 4 doesn’t mean the same thing for everyone anymore.

Can a brain tumor be cured without surgery?

In rare cases, yes. Some slow-growing, low-grade tumors in hard-to-reach areas may be monitored without surgery, especially if they’re not causing symptoms. Radiation or targeted drugs like vorasidenib can control growth for years. But for most tumors-especially high-grade ones-surgery is the first step to remove as much as possible. It’s rarely the only treatment, but it’s often essential.

How long does it take to get a brain tumor diagnosis?

With modern protocols, a diagnosis can take 7-10 business days from biopsy to final report. Molecular testing-like IDH and 1p/19q status-used to take weeks, but with new tools like the Ventana IDH1 antibody, results now come back in 48 hours. However, delays still happen due to lab capacity, insurance approvals, or geographic access, especially outside major medical centers.

What’s the difference between a benign and malignant brain tumor?

Benign tumors (like most grade 1 meningiomas) don’t contain cancer cells and don’t spread. But they can still be dangerous if they press on the brain. Malignant tumors (grades 3-4) contain cancer cells, grow quickly, invade healthy tissue, and often come back after treatment. The key is: even "benign" brain tumors can be life-threatening due to location and pressure-not because they spread like other cancers.