Most people think taking a pill for heartburn is harmless-especially if it’s over the counter. But what if that same pill is quietly making your blood pressure medicine, HIV treatment, or cancer drug stop working? It’s not science fiction. It’s happening right now to thousands of people who don’t even know it’s possible.

How Acid-Reducing Medications Change Your Body’s Chemistry

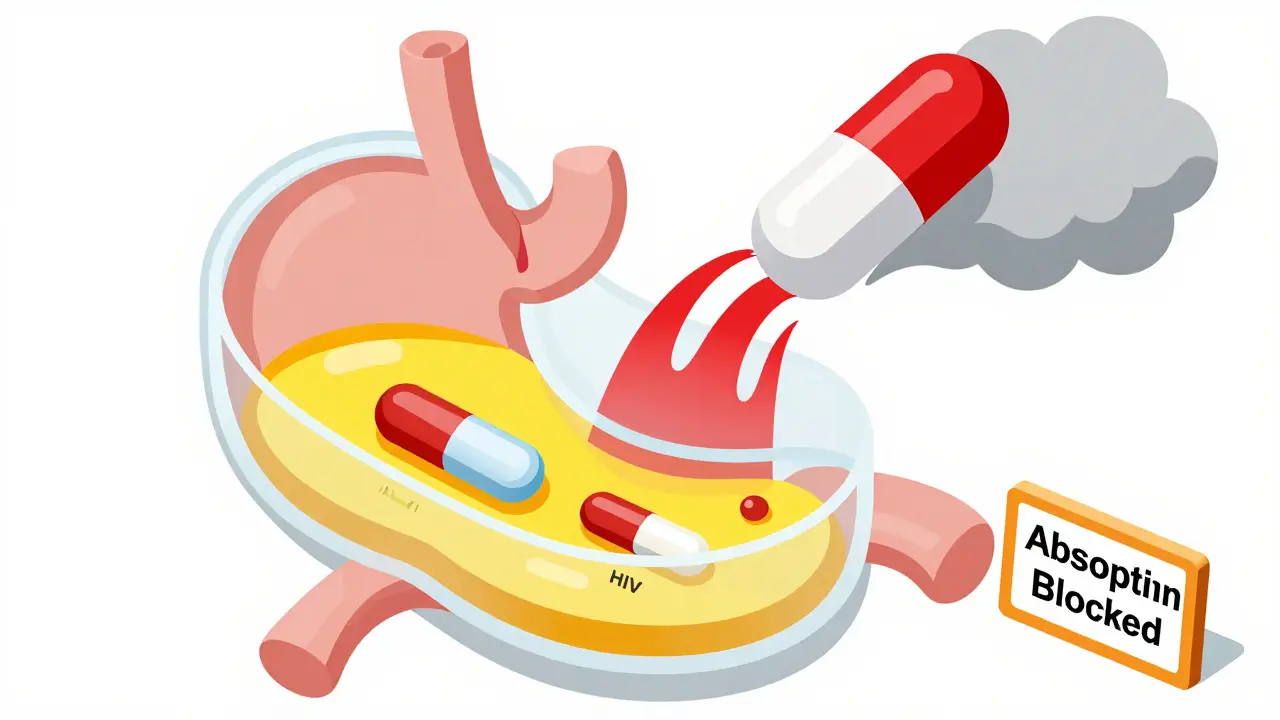

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole and esomeprazole, and H2 blockers like ranitidine and famotidine, were designed to calm stomach acid. They work by either blocking the acid-producing pumps in your stomach lining (PPIs) or shutting down the histamine signals that tell your stomach to make acid (H2 blockers). The result? Your stomach pH rises from its normal acidic level of 1.0-3.5 to around 4.0-6.0. That sounds good if you have reflux, but it’s a major problem for other drugs.Why? Because how well a drug gets absorbed depends heavily on its chemical structure and the pH of your gut. Most oral medications are either weak acids or weak bases. Weak bases-like atazanavir, dasatinib, and ketoconazole-need an acidic environment to dissolve properly. In a low-pH stomach, they turn into charged molecules that dissolve easily. But when you take a PPI, that acidic environment disappears. The drug stays neutral, doesn’t dissolve, and just passes through your gut unused.

It’s not just the stomach. While most drugs are absorbed in the small intestine, they often start dissolving in the stomach first. If they don’t dissolve there, they may never fully dissolve later. Even if they do reach the intestine, the altered pH can delay or reduce absorption. Studies show that PPIs can cut the blood levels of certain drugs by up to 95%.

The Drugs Most at Risk

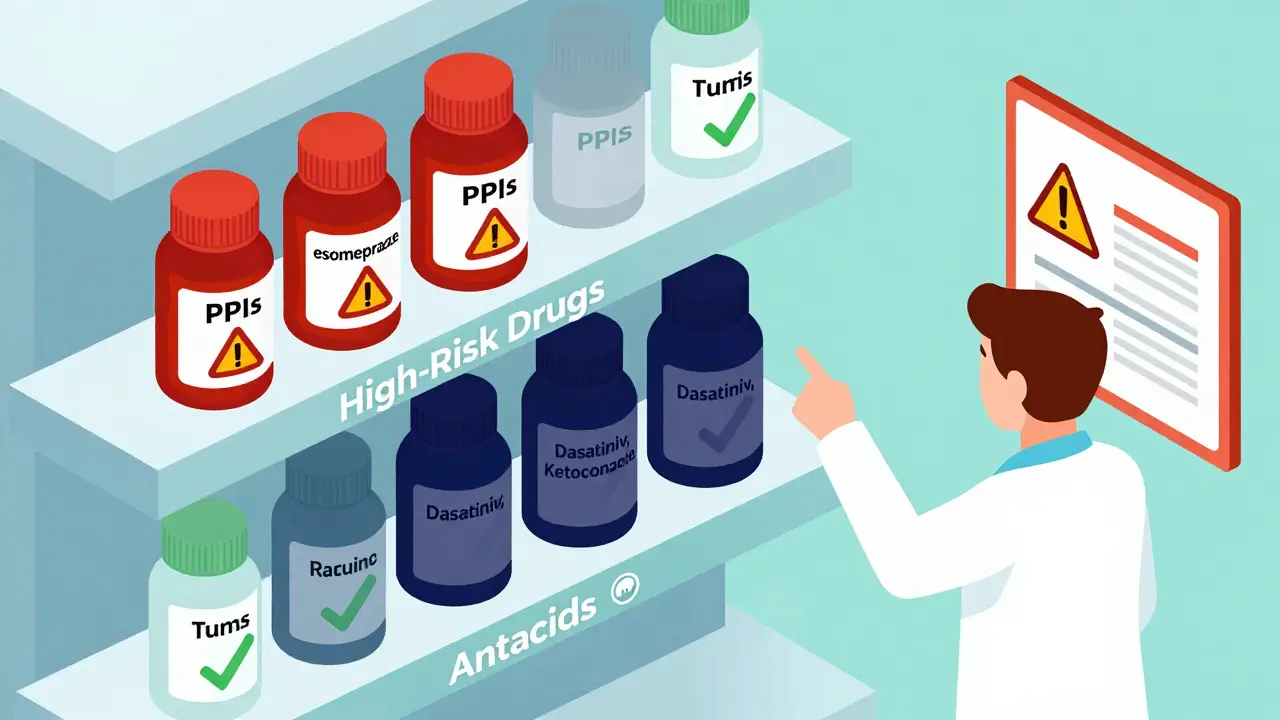

Not all drugs are affected equally. The FDA has flagged 15+ medications with clear, dangerous interactions. Here are the biggest red flags:- Atazanavir (HIV treatment): When taken with a PPI, its absorption drops by 74-95%. Patients have seen their viral load spike from undetectable to over 12,000 copies/mL. This isn’t rare-it’s well-documented.

- Dasatinib (leukemia drug): Absorption drops by about 60%. Without proper dosing adjustments, treatment fails. One study found patients on PPIs had 37% higher rates of treatment failure.

- Ketoconazole (antifungal): Almost completely ineffective when combined with PPIs. The drug just doesn’t reach therapeutic levels.

- Dasiglucagon (for low blood sugar): A rare exception. It’s a weak acid, so its absorption actually increases slightly with ARAs-but even then, it rarely causes problems.

These aren’t obscure drugs. They’re prescribed to millions. Atazanavir alone is used by over 100,000 people in the U.S. Many patients don’t realize their heartburn medication is sabotaging their life-saving treatment.

PPIs vs. H2 Blockers: Not the Same Risk

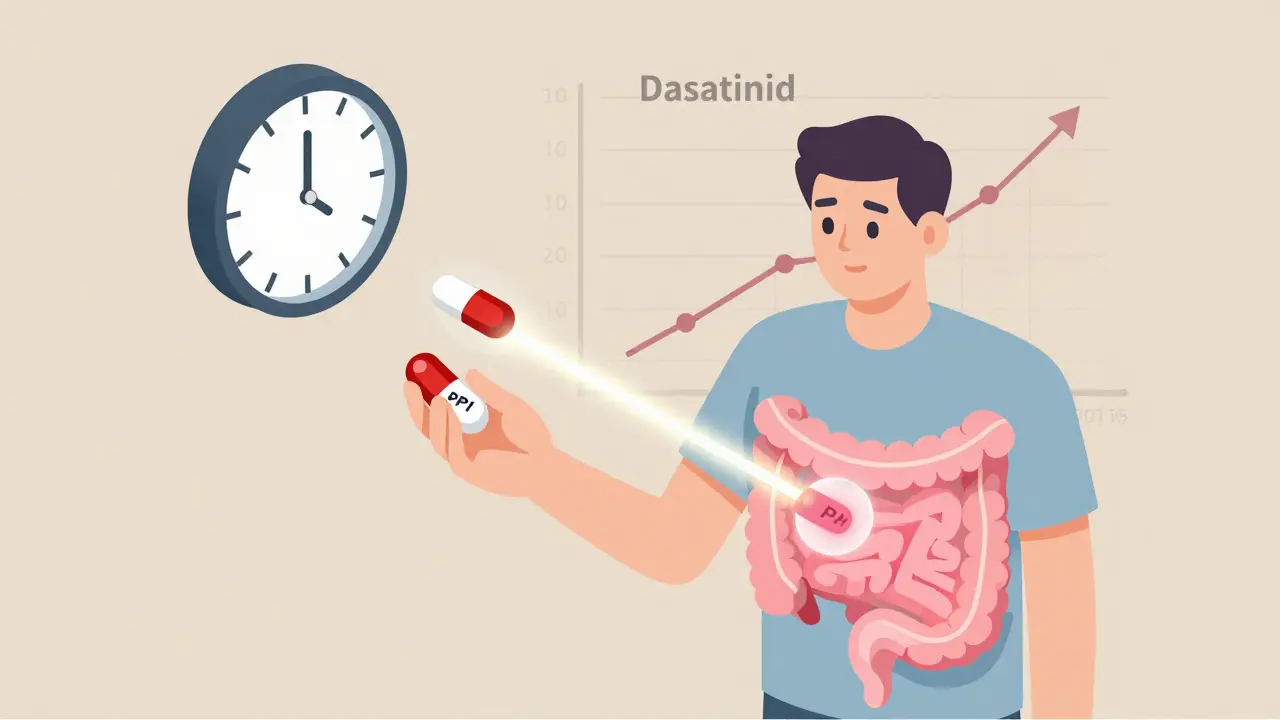

Not all acid reducers are created equal. PPIs are far more dangerous when it comes to drug interactions.PPIs suppress acid for 14-18 hours a day. They’re long-lasting and powerful. H2 blockers like famotidine only work for 8-12 hours and don’t raise pH as high. A 2024 study in JAMA Network Open found PPIs reduce drug absorption by 40-80%, while H2 blockers only cause 20-40% drops. That’s a huge difference.

Still, H2 blockers aren’t safe. If you’re on dasatinib or atazanavir, even famotidine can cause problems. The safest approach? Avoid all acid-reducing drugs unless absolutely necessary.

Why Enteric Coatings Don’t Always Help

You might think, “My pill is enteric-coated-it’s designed to bypass the stomach.” That’s true. But here’s the catch: those coatings are made to dissolve at pH 5.5 or higher. When you take a PPI, your stomach pH rises to 5.0-6.0. That means the coating can dissolve too early-in your stomach-instead of your intestine.Result? The drug gets destroyed by stomach acid or causes irritation. The FDA and Merck Manual both warn about this. Enteric coatings were meant to protect drugs from acid-but when acid is gone, the system breaks down.

Real Stories, Real Consequences

Behind every statistic is a person.One Reddit user shared how their viral load exploded after starting omeprazole for acid reflux. Their infectious disease doctor confirmed it: a textbook interaction. Another person on Drugs.com said their blood pressure meds stopped working-until they stopped taking Nexium. Their readings dropped 20 points overnight.

The FDA’s adverse event database recorded over 1,200 reports of therapeutic failure linked to acid-reducing drugs between 2020 and 2023. The top three culprits? Atazanavir, dasatinib, and ketoconazole.

On the flip side, there’s hope. A 2022 study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology showed that spacing out dasatinib and PPI doses by 12 hours restored drug levels in 85% of patients. It’s not perfect-but it works better than nothing.

What You Can Do

If you’re on any of these high-risk drugs, here’s what matters:- Check your meds. Look up every drug you take. If you’re on atazanavir, dasatinib, or ketoconazole, ask your pharmacist or doctor if you’re also taking a PPI or H2 blocker.

- Don’t stop your meds cold. If you need to stop a PPI, do it under medical supervision. Suddenly stopping can cause rebound acid.

- Try staggered dosing. If you must take both, take the affected drug at least 2 hours before the acid reducer. This helps-but it’s not foolproof.

- Consider alternatives. Antacids like Tums or Maalox work fast and don’t last long. Taking them 2-4 hours apart from your other meds can reduce risk.

- Ask about deprescribing. The American College of Gastroenterology says 30-50% of long-term PPI users don’t need them. Ask if you can cut back or stop.

Pharmacists are your best ally here. A 2023 study showed pharmacist-led reviews cut inappropriate ARA co-prescribing by 62% in Medicare patients. Don’t assume your doctor knows every interaction. Ask your pharmacist to run a full check.

The Bigger Picture

Over 15 million Americans take PPIs long-term. Many do it without a clear diagnosis. The CDC says 15% of adults in developed countries use acid reducers regularly. That’s a lot of people with altered stomach pH-and a lot of hidden drug interactions.The FDA has updated 28 drug labels since 2020 to warn about these interactions. The European Medicines Agency has done the same. But awareness is still low. In the U.S., these interactions cause an estimated 15,000-20,000 preventable treatment failures every year. That’s billions in wasted healthcare spending.

Pharmaceutical companies are responding. Nearly 40% of new drugs in development now include pH-independent delivery systems. AI tools are being built to predict interactions before they happen. But until those arrive, the responsibility falls on you and your care team.

Final Takeaway

Acid-reducing medications aren’t harmless. They’re powerful tools-but they change how your body handles other drugs. For some people, that change can mean the difference between life and death, or between control and relapse.If you’re on a medication for HIV, cancer, or serious infections, and you’re also taking a PPI or H2 blocker, don’t wait. Talk to your doctor. Ask your pharmacist. Get it checked. Your life might depend on it.

Can I still take antacids like Tums if I’m on a PPI?

Yes-but timing matters. Antacids work fast and wear off quickly, so they’re less likely to interfere than PPIs. Take them at least 2-4 hours before or after your other medications. This reduces the chance of affecting absorption. But don’t use them as a long-term replacement for PPIs without medical advice.

Why do some drugs become less effective with acid reducers while others don’t?

It depends on whether the drug is a weak acid or weak base. Weak bases (like atazanavir or ketoconazole) need acid to dissolve. In a less acidic stomach, they stay undissolved and pass through unused. Weak acids (like aspirin or dasiglucagon) dissolve better in higher pH, but they rarely cause problems because their absorption doesn’t drop enough to affect treatment. The key is the drug’s pKa and solubility.

Is it safe to take a PPI and a weak base drug if I space them out?

Spacing them out helps-but it doesn’t fix everything. Taking the drug 2 hours before the PPI can reduce the interaction by 30-40%, according to studies. But PPIs suppress acid for most of the day, so the environment stays too alkaline. For drugs like atazanavir, even spacing isn’t enough. Avoiding the combination entirely is the only reliable solution.

How do I know if my medication is affected by acid reducers?

Check the drug’s prescribing information. Look for warnings about “gastric pH,” “acid-reducing agents,” or “PPIs.” Common high-risk drugs include atazanavir, dasatinib, ketoconazole, erlotinib, and mycophenolate. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist to run a drug interaction check using a tool like Lexicomp or Micromedex.

Are over-the-counter PPIs safer than prescription ones?

No. Omeprazole, lansoprazole, and esomeprazole are the same drugs whether bought over the counter or prescribed. The dose might be lower, but the mechanism is identical. Even low-dose PPIs can significantly raise stomach pH and interfere with other medications. Don’t assume OTC means safe.

Can I switch to a different acid reducer to avoid interactions?

Switching from one PPI to another won’t help-they all work the same way. H2 blockers like famotidine are less risky but still problematic for high-risk drugs. The best option is to treat the root cause. If you’re on a PPI for heartburn, ask if lifestyle changes, weight loss, or dietary adjustments could reduce your need for it. Many people don’t need long-term acid suppression.