Melanoma Stage & Treatment Guide

Select a melanoma stage below to see recommended treatments for 2025:

Stage I

Thin tumors (< 1mm)

Stage II

Thick tumors (1-4mm)

Stage III

Regional lymph node involvement

Stage IV

Distant metastasis

Select a stage above to view treatment recommendations for 2025.

Key Takeaways

- Early‑stage melanoma is often cured with surgery alone; later stages need systemic therapy.

- Immunotherapy, especially PD‑1 inhibitors, dominates first‑line treatment for stage III‑IV disease in 2025.

- Targeted therapy works best for patients with BRAF‑mutated tumors, and can be combined with immunotherapy for higher response rates.

- Radiation and chemotherapy are now niche options, mainly for palliation or specific clinical‑trial scenarios.

- Discussing genetics, side‑effect profiles, and quality‑of‑life goals with your oncologist helps you pick the right mix.

When a melanoma diagnosis lands on your doorstep, the flood of treatment jargon can feel overwhelming. This guide cuts through the noise, laying out every major option available in 2025-from the scalpel to the latest checkpoint inhibitors-so you know what to expect, when to ask questions, and how to weigh the pros and cons.

Melanoma is a malignant skin cancer that arises from pigment‑producing melanocytes. It accounts for roughly 1% of all cancer cases worldwide but is responsible for the majority of skin‑cancer deaths because of its ability to spread quickly. Treatment decisions hinge on three clinical pillars: the tumor’s stage, its genetic makeup, and the patient’s overall health and preferences.

How Staging Directs the Treatment Roadmap

Doctors use the AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) 8th edition staging system, which groups melanoma into four stages:

- Stage I: Thin tumors (<1mm) without ulceration; usually cured with surgery.

- Stage II: Thicker or ulcerated lesions; surgery plus possible sentinel‑node biopsy.

- Stage III: Spread to regional lymph nodes; systemic therapy (immuno‑ or targeted) becomes standard.

- StageIV: Distant metastases; combination systemic regimens are the mainstay.

Understanding your stage tells you whether a scalpel, a drug, or both will be in your treatment plan.

Surgical Options: Cutting Out the Cancer

Surgery is a local, invasive procedure that removes the primary tumor and, when indicated, nearby tissue or lymph nodes. In 2025, surgery remains the gold standard for stagesI‑II and for resectable metastases in stageIII‑IV.

- Wide Local Excision (WLE): Removes the tumor with a 1‑2cm margin of healthy skin. Pathology confirms clean margins.

- Mohs Micrographic Surgery: Layer‑by‑layer removal with immediate microscopic analysis. Ideal for melanomas on the face or hands where tissue preservation matters.

- Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SLNB): A minimally invasive test to see if cancer has reached the nearest node. Positive nodes may lead to a complete lymph node dissection or adjuvant systemic therapy.

- Metastasectomy: Surgical removal of isolated distant lesions (lung, brain, liver) when they are few and can be fully resected.

Recovery time varies-most outpatient procedures need a week of wound care, while extensive nodal surgery may require a few weeks of limited activity.

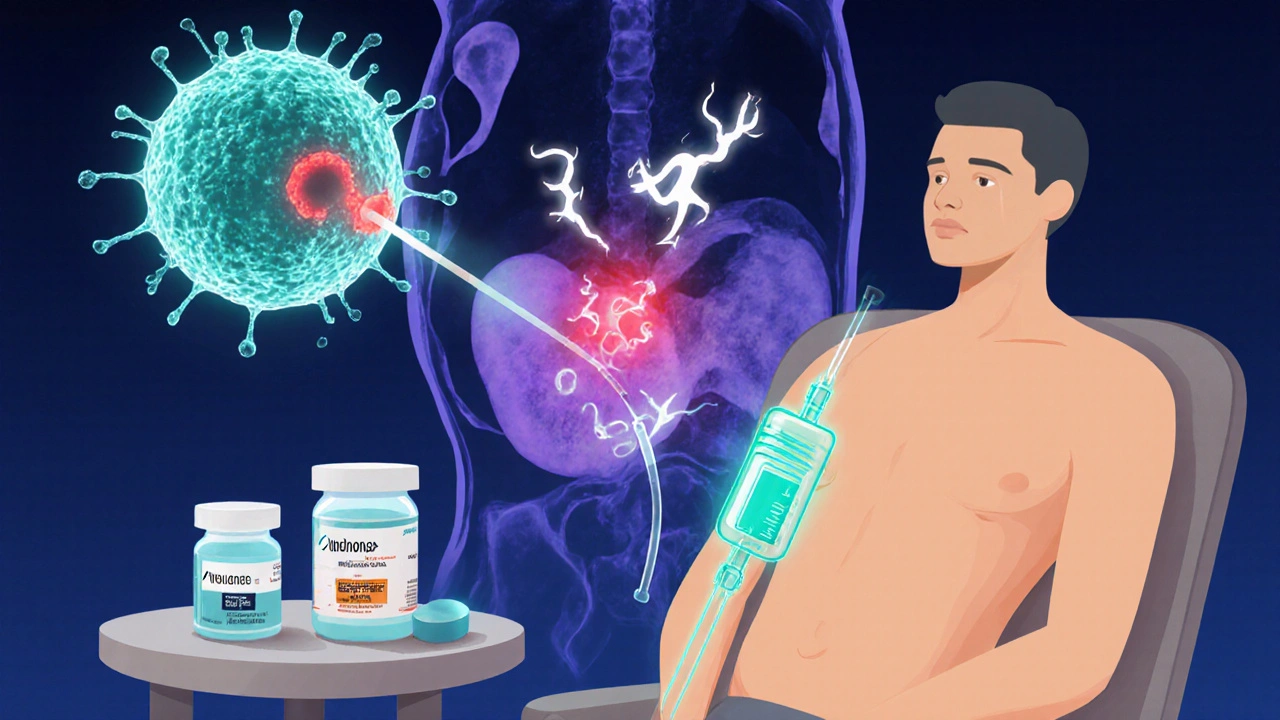

Immunotherapy: Enlisting the Immune System

Immunotherapy is a treatment that boosts or restores the body’s natural immune response against cancer cells. Since the FDA’s 2014 approval of ipilimumab (CTLA‑4 blocker), the field has exploded. In 2025, the most commonly used agents are PD‑1 inhibitors.

- Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and Nivolumab (Opdivo): Bind PD‑1 on T‑cells, preventing tumors from shutting them down. They improve 5‑year overall survival to around 45‑50% for stageIII‑IV patients.

- Combination PD‑1 + CTLA‑4 (nivolumab + ipilimumab): Offers higher response rates (≈60%) but doubles the risk of immune‑related adverse events such as colitis, hepatitis, and endocrine dysfunction.

- Adjuvant Immunotherapy: Given after surgery for high‑risk stageIIIB‑C or stageIII patients to lower recurrence risk.

Side‑effects usually appear within weeks and are managed with steroids or hormone replacement. Most patients stay on therapy for up to two years unless disease progresses.

Targeted Therapy: Hitting the Cancer’s Achilles Heel

Targeted therapy is a drug that interferes with specific molecular pathways that drive tumor growth. About 40‑50% of melanomas harbor a BRAF V600 mutation, making them eligible for BRAF/MEK inhibition.

- BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib): Block the mutated BRAF protein, halting MAPK pathway signaling.

- MEK inhibitors (trametinib, cobimetinib): Usually combined with BRAF blockers to prevent resistance.

- Combination regimens: BRAF + MEK + PD‑1 inhibitor (e.g., dabrafenib + trametinib + pembrolizumab) are under PhaseIII trials with early data showing 70% response rates and longer progression‑free survival.

Targeted therapy works fast-tumors can shrink within weeks-but resistance often emerges after 6‑12 months, prompting a switch to immunotherapy or clinical‑trial enrollment.

Radiation and Chemotherapy: When Traditional Tools Still Matter

Radiation and chemotherapy are no longer frontline for most melanomas but retain niche roles.

- Radiation therapy: Used for brain metastases (stereotactic radiosurgery) or painful bone lesions. It can also act as an adjuvant after incomplete surgical margins.

- Chemotherapy: Agents like temozolomide are largely replaced by immuno‑ and targeted drugs, yet may be employed when patients cannot tolerate newer agents.

- Oncolytic virus therapy (T‑VEC): A genetically engineered herpes virus injected into cutaneous metastases, prompting local tumor lysis and systemic immune activation. Approved in the EU in 2023, it’s now a supplemental option for injectable disease.

Both modalities carry classic side effects-fatigue, skin irritation, nausea-so they’re chosen only when benefits outweigh the burden.

Choosing the Right Mix: Decision‑Making Framework

Because melanoma treatment is increasingly personalized, consider the following checklist during your oncology consult:

- Genetic testing: Confirm BRAF, NRAS, KIT status. Ask if next‑generation sequencing is available.

- Stage assessment: Ensure full imaging (PET‑CT, brain MRI) to identify all disease sites.

- Fitness evaluation: Discuss comorbidities, organ function, and performance status (ECOG score).

- Treatment goals: Curative intent vs. disease control vs. quality of life.

- Side‑effect tolerance: Weigh immune‑related toxicities against the convenience of oral targeted pills.

- Clinical trial availability: Many 2025 studies explore triple‑combo regimens or novel checkpoint molecules (LAG‑3, TIM‑3).

Putting a spreadsheet together-stage, mutation, preferred systemic option, surgical feasibility-helps you stay organized and ask targeted questions.

Comparison of Major Treatment Modalities (2025)

| Modality | Typical Stage | Invasiveness | Main Benefit | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery (WLE, Mohs) | I‑II (occasionally resectable III/IV) | High (incision, anesthesia) | Potential cure for localized disease | Wound infection, scar, lymphedema (node removal) |

| PD‑1 Immunotherapy (pembrolizumab, nivolumab) | III‑IV | Low (IV infusion) | Durable responses, survival benefit | Fatigue, rash, colitis, thyroiditis |

| Combination PD‑1 + CTLA‑4 | III‑IV (high‑risk) | Low | Higher response rate than PD‑1 alone | Severe immune toxicity (≈30% grade3‑4) |

| BRAF + MEK Inhibitors | III‑IV (BRAF‑mutated) | Low (oral pills) | Rapid tumor shrinkage | Fever, joint pain, skin rash, cardiomyopathy (rare) |

| Radiation (SRS, EBRT) | III‑IV (brain, bone, unresectable nodes) | Medium (device‑based) | Local control, pain relief | Fatigue, skin erythema, neuro‑cognitive changes (brain) |

What to Expect After Starting Treatment

Regardless of the chosen pathway, follow‑up is a constant. Typical schedules look like this:

- Post‑surgery: Clinic visit at 2weeks for wound check, then every 3‑6months for imaging.

- Immunotherapy: Infusions every 2-3weeks for the first year, then every 4-6weeks if disease remains stable.

- Targeted pills: Daily oral dosing; lab work every month to monitor liver enzymes and ECG.

Any new symptom-persistent cough, vision change, severe fatigue-should trigger an immediate call to your care team.

Future Directions: What’s on the Horizon for 2026 and Beyond?

Researchers are now testing next‑generation checkpoint molecules (LAG‑3, TIGIT) and personalized neo‑antigen vaccines that teach the immune system to recognize a patient’s unique tumor signatures. Early PhaseI data suggest response rates above 80% when combined with PD‑1 blockade.

Adoptive cell therapy, especially tumor‑infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) expanded ex vivo, is moving from specialty centers into broader clinical practice, offering another lifeline for patients who progress after standard immunotherapy.

While these innovations are still trial‑phase, they signal that the era of ‘one‑size‑fits‑all’ melanoma care is ending, replaced by hyper‑personalized regimens driven by genetics and immune profiling.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can early‑stage melanoma be cured with surgery alone?

Yes. For stageI and most stageII lesions, wide local excision with clear margins typically yields a cure rate above 95% when no nodal involvement is found.

What is the difference between PD‑1 and CTLA‑4 inhibitors?

PD‑1 blockers (pembrolizumab, nivolumab) release the “brakes” on T‑cells at the tumor site, while CTLA‑4 inhibitors (ipilimumab) act earlier in the immune activation process, affecting T‑cell priming in lymph nodes. PD‑1 agents are generally better tolerated; CTLA‑4 adds potency but more severe immune‑related toxicity.

Should I get tested for BRAF mutations even if my melanoma is thin?

Guidelines recommend genetic testing for all melanomas ≥0.8mm thickness or any tumor that recurs. Knowing your BRAF status helps plan adjuvant therapy should the cancer spread.

How long do I stay on immunotherapy after surgery?

Adjuvant PD‑1 therapy is typically given for up to 12months post‑surgery in high‑risk stageIII patients. For metastatic disease, many oncologists continue for up to two years, stopping earlier if toxicity or progression occurs.

Are there lifestyle changes that improve treatment success?

Maintaining a healthy weight, quitting smoking, and limiting UV exposure help the immune system function optimally. Some studies show that regular moderate exercise may reduce immunotherapy side effects, though it’s not a substitute for medical therapy.