Pneumonia Gut Recovery Estimator

Estimate how long it might take for your gut health to recover after pneumonia based on your specific situation. This tool uses information from recent medical research to provide personalized guidance.

Your Recovery Factors

Estimated Recovery Time

Your Recovery Tips

Key Takeaways

- Respiratory infections can disrupt gut barrier function and trigger nausea, loss of appetite, and diarrhea.

- The body’s immune response to pneumonia releases inflammatory chemicals that reach the stomach and intestines.

- Antibiotics used to treat pneumonia often alter the gut microbiome, sometimes causing lasting digestive issues.

- Probiotics, gentle diets, and staying hydrated can ease stomach problems while the lungs heal.

- Seek medical help if digestive symptoms are severe, sudden, or accompanied by fever or dehydration.

Why a Lung Infection Can Turn Your Stomach Upside‑Down

When a person contracts Pneumonia is a lung infection caused by bacteria, viruses, or fungi that inflames the air sacs and interferes with oxygen exchange, the body doesn’t keep the reaction confined to the chest. The immune system launches a cascade of chemicals - cytokines, prostaglandins, and acute‑phase proteins - that circulate through the bloodstream. These messengers are designed to recruit white blood cells to the lungs, but they also reach the Digestive System is the network of organs that break down food, absorb nutrients, and expel waste. As a result, you may notice nausea, reduced appetite, or even loose stools while your lungs are fighting the infection.

Inflammation: The Bridge Between Lungs and Gut

The body’s Immune Response is a series of coordinated actions by immune cells and signaling molecules that protect against pathogens is a double‑edged sword. In pneumonia, immune cells release high levels of Inflammation is a protective response involving blood vessels, immune cells, and molecular mediators that aims to eliminate the cause of cell injury. While this protects lung tissue, it also compromises the gut lining, making it more permeable - a condition often called “leaky gut.” A leaky gut allows bacterial fragments and toxins to slip into the bloodstream, which can further fuel systemic inflammation and worsen digestive discomfort.

Gut Microbiome Gets Shaken

Your Gut Microbiome is the community of trillions of bacteria, viruses, and fungi living in your intestines that help digest food and regulate immunity thrives on a stable environment. During pneumonia, two main forces upset this balance: the inflammatory surge and the antibiotics prescribed to kill the offending pathogen. Studies from 2023‑2024 show that up to 60% of pneumonia patients develop a temporary dip in beneficial bacterial groups like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. This depletion can lead to bloating, gas, and irregular bowel movements, sometimes persisting weeks after the infection clears.

Antibiotics: Hero and Villain

Most bacterial pneumonias are treated with broad‑spectrum Antibiotics are drugs that kill or inhibit the growth of bacteria and are commonly prescribed for infections. While they target the lung‑invading microbes, they also indiscriminately wipe out good bacteria in the gut. The result is a classic case of “antibiotic‑associated diarrhea.” In severe cases, patients can develop Clostridioides difficile infection, which may require a second round of targeted antibiotics and can be life‑threatening.

Vaccination: Preventing the Chain Reaction

Prevention works best. The Vaccination is the administration of a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular disease against common pneumonia‑causing pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcal vaccine) and influenza viruses (flu shot) dramatically reduces the risk of severe lung infection and, by extension, the downstream digestive fallout. In the UK, the pneumococcal vaccine is offered to adults over 65 and younger people with certain health conditions, cutting hospitalization rates by roughly 40%.

Practical Ways to Protect Your Stomach While Recovering

- Hydrate smartly: Sip clear fluids - water, oral rehydration solutions, or weak tea - throughout the day. Avoid sugary drinks that can feed harmful gut bacteria.

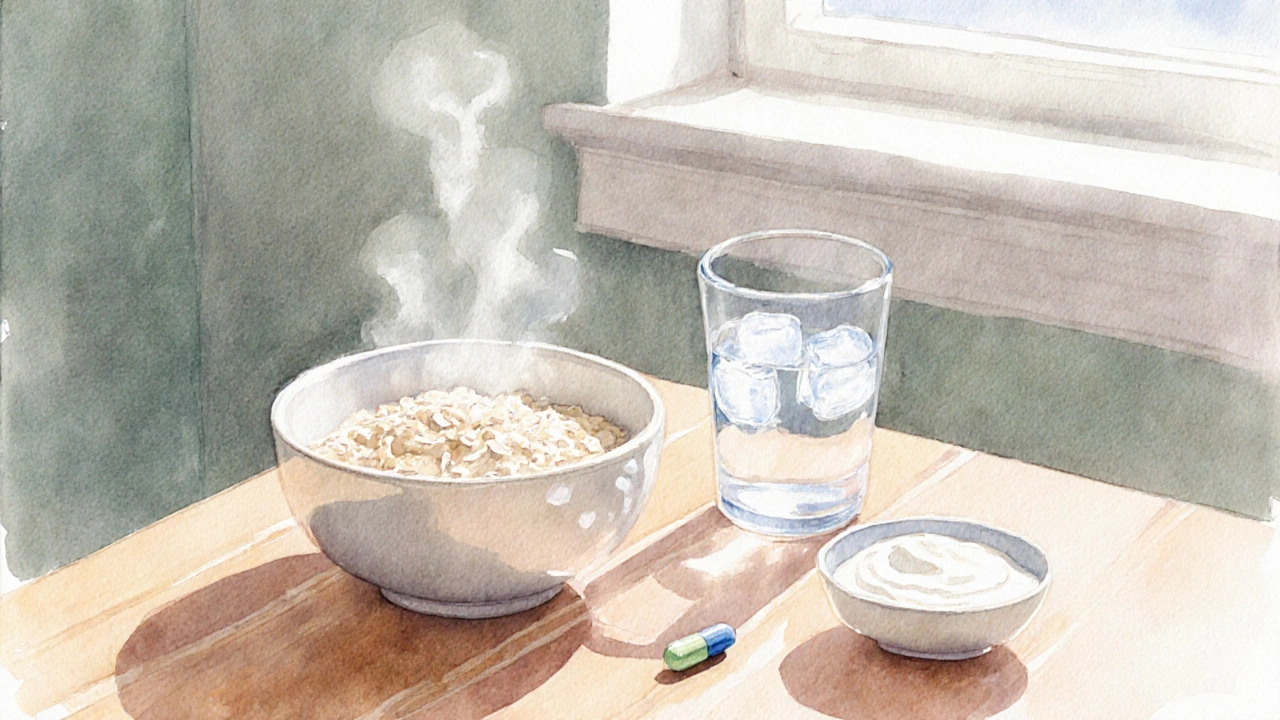

- Eat gut‑friendly foods: Choose bland, easy‑to‑digest meals like boiled potatoes, steamed carrots, and plain oatmeal. Add a tablespoon of fermented foods (yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut) if you tolerate them.

- Consider probiotics: A daily probiotic containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG or Saccharomyces boulardii can replenish beneficial microbes and shorten diarrhea duration.

- Limit irritants: Skip alcohol, caffeine, and spicy foods until your appetite returns and bowel movements normalize.

- Monitor antibiotic side effects: If you notice persistent watery stools, abdominal cramping, or blood in stool, contact your doctor - you may need a stool test or a different antibiotic.

When Digestive Symptoms Signal a Complication

Most stomach upset during pneumonia resolves as the lungs heal, but watch for red flags:

- Persistent vomiting preventing fluid intake.

- Diarrhea lasting more than five days or accompanied by fever.

- Severe abdominal pain, especially if it spreads to the back.

- Signs of dehydration: dry mouth, dizziness, reduced urine output.

- Sudden weight loss or loss of appetite beyond the first week.

If any of these appear, seek medical assessment promptly. Early intervention can prevent dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and secondary infections.

Comparison: How Different Respiratory Illnesses Affect Digestion

| Illness | Typical Digestive Symptoms | Inflammatory Strength | Antibiotic Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | Nausea, loss of appetite, diarrhea, abdominal cramping | High - systemic cytokine surge | Often required (broad‑spectrum) |

| Influenza | Occasional nausea, mild stomach upset | Moderate - systemic but shorter‑lived | Rarely prescribed (viral) |

| Common Cold | Very mild or none | Low - localized to upper airway | Never prescribed |

Bottom Line

While pneumonia is primarily a lung disease, its ripple effects reach the gut through inflammation, immune signaling, and medication side effects. Understanding this connection helps you spot warning signs early, choose supportive foods, and discuss probiotic options with your clinician. A proactive approach can keep your digestion humming even while your lungs take the hit.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can pneumonia cause long‑term gut problems?

Most digestive issues resolve within a few weeks after the infection clears. However, if you had a severe bout of pneumonia or multiple courses of antibiotics, the gut microbiome may take longer to rebalance, sometimes requiring a targeted probiotic regimen.

Should I take probiotics while on antibiotics for pneumonia?

Many clinicians recommend a probiotic that contains Lactobacillus or Saccharomyces species taken a few hours after the antibiotic dose. This timing helps protect beneficial gut bacteria without interfering with the drug’s effectiveness.

Why does nausea happen even if the infection is in the lungs?

The cytokine storm triggered by pneumonia reaches the brain’s vomiting center and the gut’s enteric nervous system, which can stimulate nausea and reduce appetite.

Is there a way to prevent digestive side effects without skipping antibiotics?

Yes. Stay hydrated, choose a bland diet, and add a probiotic supplement. Discuss any concerns with your doctor before altering the antibiotic course.

How effective is the pneumococcal vaccine at stopping these gut issues?

By preventing severe pneumonia in the first place, the vaccine indirectly stops the cascade of inflammation and antibiotic use that can upset the gut. In vaccinated adults, hospital‑acquired digestive complications drop by about 30‑40%.